Omaha District's Recreation Mission

|

|

Omaha District Photo - Graphic Restoration by Al Barrus

|

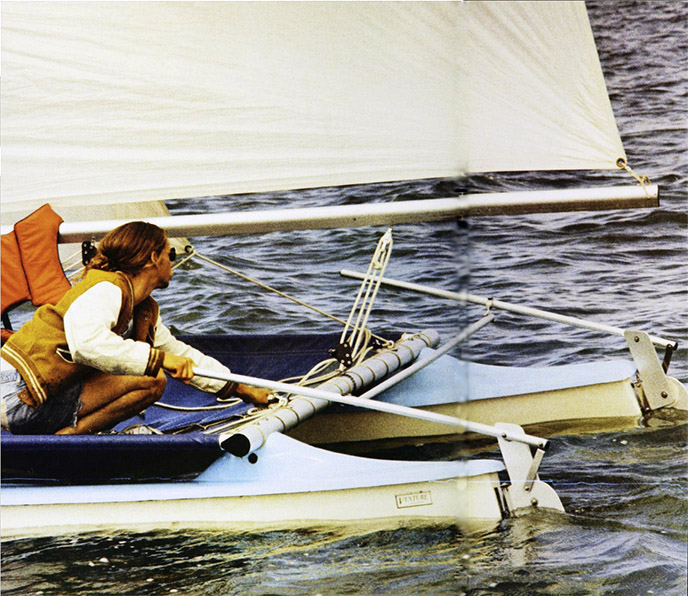

The Pick-Sloan plan ushered in an era of river and reservoir development that gave a prominent place to the recreational use of impounded waters. Section 4 of the Flood Control Act of 1944 authorized the Corps of Engineers "to construct, maintain, and operate public park and recreational facilities in reservoir areas" under its jurisdiction. The law specified that the waters of Corps reservoirs should be "open to public use generally, without charge, for boating, swimming, bathing, fishing, and other recreational purposes." Except in cases where recreational use was for some reason contrary to the public interest, the legislation required the Corps to provide ready access to the shores of reservoirs and empowered the Engineers to make rules governing the use of the waters.

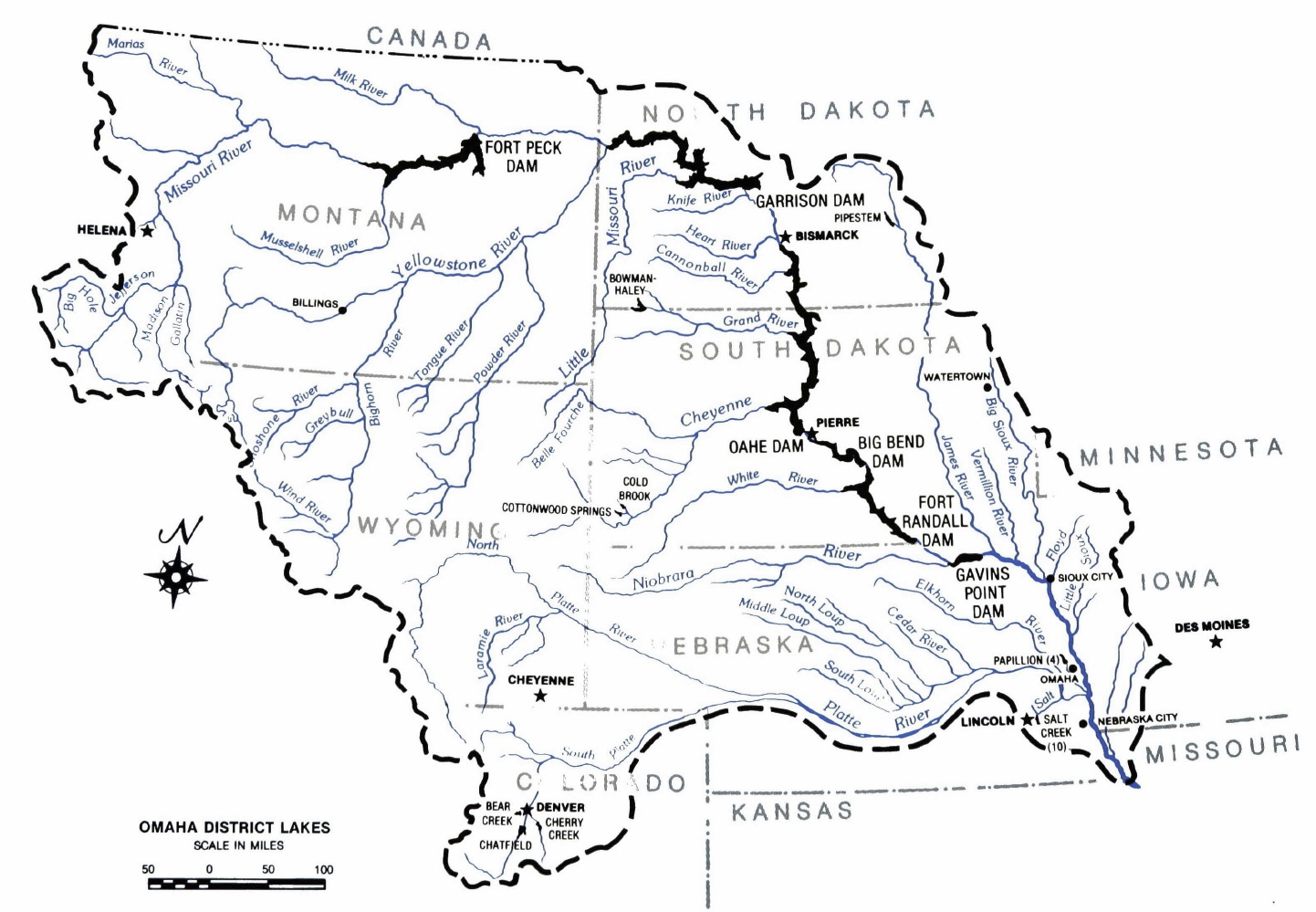

The planners of the first main stem dam and reservoir at Fort Peck in Montana gave little thought to recreation when they undertook their project. In later years, the District gave careful attention to the recreational use of the reservoirs and lands behind the main stem Missouri and Denver-area dams. The Missouri River main stem lakes have been referred to as the greatest chain of man-made lakes in the world. Omaha District started a number of programs which enhanced leisure activities in the basin, most notably the construction of 144 recreation areas on the larger reservoirs and similar facilities on smaller urban flood control projects such as Salt Creek and Papillion Creek. The dams and reservoirs evolved into a huge recreational complex based on the PickSloan plan. The many miles of shoreline and numerous surface acres of water behind the dams dramatically changed water sports in the Missouri River basin.

Recreational use of the structures actually began when visitors came to the damsites during their construction phases. They watched the work from hot and dusty overlooks. At Oahe Dam in South Dakota, for example, over 90,000 sidewalk superintendents came to watch the building of the structure in 1957. The lack of shade trees, campsites, and picnic areas did not deter them.

|

|

Omaha District Photo

|

Public demand for rapid development of the recreational potential of the reservoirs soon emerged. In the case of Lewis and Clark Lake behind Gavins Point Dam in South Dakota, civic groups and sportsmen clamored to obtain waterfront land for a variety of purposes. Some South Dakotans found the development of huge Lake Texoma on the border between Texas and Oklahoma instructive and urged similar projects for their State. Soon the concept of the Missouri Great Lakes became popular, and the Missouri Great Lakes Association formed to promote the development and use of the reservoirs.

The legislative basis for this huge recreation program evolved from the Flood Control Act of 1944. The Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act of 1958 made wildlife conservation an essential element of project planning. The act provided that "wildlife conservation shall receive equal consideration and be coordinated with other features of water-resource development programs through the effectual and harmonious planning, development, maintenance, and coordination of wildlife conservation and rehabilitation . "Also included were provisions for public shooting and fishing areas and for easements across public land for access.

In 1961, President John Kennedy asked the heads of Federal agencies responsible for development of water resources to review their standards for the formulation and evaluation of projects. He also wanted their recommendations for changes. As a result, the Secretaries of Agriculture; the Interior; Health, Education, and Welfare; and the Army prepared a set of recommendations for judging the costs and benefits of projects. The types of primary benefits included recreation benefits, quantified on the basis of a simulated market giving weight to all pertinent considerations, including charges for comparable recreational opportunities at private facilities.

On the last day of May 1962, President Kennedy accepted the suggestions. Two weeks later, the Chief of Engineers' office in Washington issued implementing instructions to division and district engineers. From that point, recreation became part of the benefit-cost ratio used to justify projects on an economic basis.

|

|

Omaha District Photo

|

Several years later, the Federal Water Project Recreation Act incorporated recreation considerations into project planning. The act specified that investigations of potential projects, whether intended for multiple uses or for specific items such as navigation, flood control, power generation, or reclamation, should consider fully the potential use of the project either for recreation or fish and wildlife enhancement. In addition, the act required coordination of recreation plans with state and local governments and encouraged construction agencies to turn over to non-Federal public bodies the administration of recreation and wildlife enhancement on project lands and waters. As a consequence of this law, recreation became one of the legitimate purposes for construction and operation of multiple-purpose projects.

On some of its earlier projects, the District left the trees that grew on reservoir sites standing and drowned them when the reservoirs filled. At Lewis and Clark Lake, this practice created hazards for boaters who brought unexpectedly large and fast watercraft to the lake. The District was forced to mark safe channels with buoys.

Timber clearance was necessary for safe operation of powerplants as well as for protection of boaters. At Fort Randall in South Dakota, the District and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service cooperated in determining the best area to clear for balanced reservoir operation. The District left uncut habitat areas requested by the Service as well as the trees along the riverbed that marked deep water. Slashed limbs were cleared only from heavily used recreation areas. All together, the 6-year operation cleared 51,000 acres. For Oahe, the Omaha Engineers cleared 1,380 acres at Mobridge and Pollock, South Dakota; Fort Yates, North Dakota; and Bear Creek to create safe boating areas, eradicate mosquito breeding grounds, remove dead trees, and provide access for depth soundings.

Reservoir operations required tree planting as well as removal. At five different Oahe locations, the District planted honeysuckle, pine, olive, elm, cherry, and ash trees to provide pleasant surroundings for recreational users of the lake. Newly planted trees also protected game birds and deer. Some plantings, based on the Department of Agriculture's experience with shelterbelts during the 1930's, were intended as windbreaks.

The energy crisis of the 1970's brought an increased demand for firewood and changed timber management at the reservoirs. The shelterbelts and other stands of timber became attractive as sources of fuel. One pheasant hunter complained that the shelterbelts seldom yielded any game; he always found that "some nut with a chainsaw had scared all the birds away."

|

|

Omaha District Photo

|

With large numbers of trees within the reservoir boundaries being cut, the District established a policy to protect the woods, wildlife, and users. The Omaha District prohibited wood gathering in some reservoir areas and limited it to the taking of driftwood and fallen timber in others. Fines were imposed for violations.

By 1980, the recreation sites along Lake Oahe alone numbered 40. The District operated 37 of them; Burleigh County, North Dakota, ran 2; and the town of Pollock managed the other. As the number of sites grew, the facilities and activities expanded. On some summer evenings, rangers offered programs in the Cottonwood Amphitheater below the dam. Tours through the dam were available, and the powerhouse visitor center contained models that showed construction and operation. The District provided many facilities for boaters but could not guarantee availability. During the low-water year of 1980, the main stem dams had to continue releasing water for power generation and navigation. By the middle of the summer, Oahe's pool dropped 7 feet, leaving some docks high and dry. By the end of the summer, the lake went down another 3 feet.

On Lake Sharpe behind Big Bend Dam in South Dakota, recreational use increased dramatically over the years. Also, the type of visitors and equipment that came to the reservoir changed. Many people brought large recreational vehicles equipped with full utility systems. Facilities with water, electricity, and sanitary hookups were built to accommodate the wheeled behemoths.

|

|

South Dakota Fish and Wildlife Services photo

|

The tailrace below Big Bend Dam was intended to be a major recreation area even while construction was starting. Chalkstone dumped into the tailrace from the powerhouse excavation formed a peninsula and a boat basin which was protected from the discharge of the turbines by the artificial barrier. A 40-unit campground was bu ilt and furnished with picnic tables, fireplaces, wells, comfort stations, and a dock.

The recreation facilities at the Colorado dams differ somewhat from those on the main stem . Because they are near Denver, Bear Creek, Cherry Creek, and Chatfield Lakes draw largely day users instead of overnight visitors. Consequently, the reservoir areas are designed with golf courses and rifle ranges, along with numerous paths for riding, hiking, and cycling. Chatfield has a marina and sailboat harbor as well as an equestrian center.

From 1950 to 1965, 113 people drowned in Omaha District reservoirs. The District and local governments made a concerted effort to explain and enforce water safety on the lakes. Starting in 1971, a Coast Guard boating detachment assigned to Federal recreational waters in North and South Dakota, Wyoming , and Colorado aided in this effort. The detachment had considerable law enforcement authority but gave its highest priority to boating safety and assistance. It also organized an auxiliary detachment of private citizens to help with the work. The Coast Guard unit was withdrawn from the reservoirs in 1980.

Because the main stem reservoirs were in sparsely populated areas, the District was able to provide land on which interested citizens could build recreation homes. The Omaha District set aside two summer cottage areas along Lake Sakakawea behind Garrison Dam in North Dakota, near Riverdale and Garrison. The original 1/3-acre lots sold for between $100 and $525. Purchase contracts required that buyers place structures no smaller than 320 square feet on the lots within 3.5 years.

|

|

Omaha District Photo

|

In the early 1960's, this practice was discouraged. The emphasis turned strongly toward maintenance of water and land areas at projects for the use of the general public. Private use of project area lands was designated a very low-priority interim use.

The areas in which the dams are located have considerable historic significance. The District built visitor centers and installed displays at the dams to explain the history of the immediate region as well as the projects, their benefits, and the recreational opportunities available. Narratives were designed to assist visitors in understanding the role of the Corps of Engineers and the benefits and costs of the particular project and to aid them in their use and enjoyment of project facillties.

Some of the reservoirs are located near historical sites of particular interest. Gavins Point is just upstream from Calumet Bluff, where Lewis and Clark first met the Sioux Indians. The visitor center, built atop the bluff, offers a panoramic view of the project. From Gavins Point Dam downstream 58 miles to Ponca State Park, Nebraska, is one of the few remaining natural reaches of the Missouri River. This stretch of river, known as the Missouri National Recreational River, is a major recreational resource, offering boating, fishing, camping, picnicking, hunting, and other outdoor activities. It is also valuable because of its outstanding natural, historic, cultural, and esthetic values. Fort Randall Dam is near Christ Church, which was erected by soldiers from the garrison of old Fort Randall during the 1870's and visited by such frontier personages as Jim Bridger, Bill Cody, General Philip Sheridan, and Sitting Bull. Lightning damaged the church in 1905, but 48 years later, the Omaha District stabilized the imposing remains.

|

|

Omaha District Photo

|

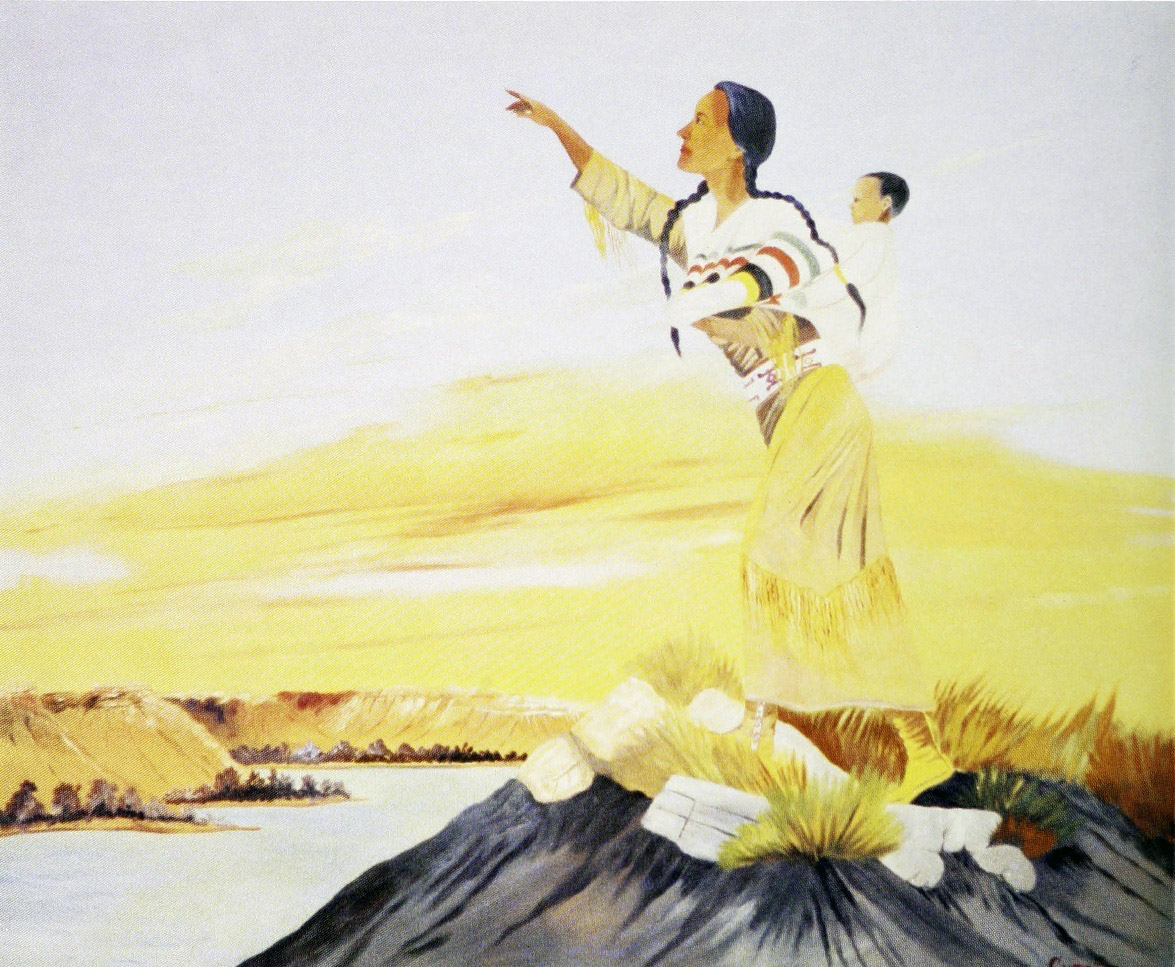

Some of the visitor centers contain dramatic art works describing the local heritage. At Gavins Point, a mural depicts the evolving role of the Corps of Engineers on the Missouri. The painting starts with Lewis and Clark, who as Government explorers and not as Engineers, performed a mission later carried out by officers of the Corps of Engineers and the Corps of Topographical Engineers. The scene shifts over time-through the long years of trying to provide a navigation channel, surveying, and constructing the big dams to developing recreation facilities and fish and wildlife conservation. Lewis and Clark were also on an artist's mind at Garrison, where a Hidatsa Indian artist, Clarence Cuts The Rope, painted a mural depicting Sacajawea, who guided Lewis and Clark's expedition over the Rocky Mountains to the headwaters of the Columbia River.

At Fort Peck, in addition to showing models of the dam's operation, the visitor center in the powerhouse contains a paleontological museum. The dam was built in an area rich in fossils, and the museum collection grew based on contributions from workers as well as scholars. The operations crew at the dam continued the tradition and added to the museum such exotica as the horn core of a triceratops, a fossil egg, and an ancient lobster. The District also maintained a small herd of buffalo at Fort Peck at the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge.

Wildlife protection and management also became a function of the projects after passage of the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act in 1958. At Big Bend, the U-shaped lake bottom provided a well-balanced deep and shallow water environment for wildlife. The isolation of the project also made it a good location for development of habitat areas. The area rimming the reservoir, which lacked cover, was developed into a refuge for pheasant and grouse. All told, 11,000 acres at Big Bend were set aside for wildlife protection.

|

|

Christ Church at Fort Randall. Oil by Eugene Kingman, 1909-1975

|

The main stem reservoirs were constructed across the path of the great central flyway, the route used by numerous species of migrating birds. Every year, Canadian and snow geese use the flyway, as do pintails, canvasbacks, mallards, and others. Ospreys, turkey vultures, bald eagles, and golden eagles are found at the reservoirs. The lakes also lure cormorants, usually considered to be Asian birds, which roost on the trees inundated by the waters. The District cooperates in the protection of these birds by providing breeding grounds and habitat.

Rare and endangered species find protection at Corps reservoirs. Within the Oahe area, endangered species include the black-footed ferret, blacktailed prairie dog, burrowing owl, osprey, peregrine falcon, and whooping crane. Ospreys and turkey vultures soar over Lewis and Clark Lake or perch on the chalk cliffs. Eagles·winter over the open tailwaters at Gavins Point. At Chatfield Lake in Colorado, a grove of cottonwoods planted by the District form part of a rookery used by blue herons.

At Fort Randall, the tumbling waters passing through the dam keep the tailwaters free of ice and lure eagles to feed on the fish. The Corps protects this newly found feeding area for bald and golden eagles from erosion caused by the rushing water. The National Wildlife Federation and Southland Corporation supported the effort by contributing land for the roost. The 600-acre site became the Karl E. Mundt National Wildlife Refuge and a registered national landmark.

|

| Sacagawea by Clarence Cuts The Rope at Garrison Dam |

Fishing opportunities at the main stem reservoirs attract many people. Walleye, sauger, catfish, northern pike, bass, and crappie swim in the lakes, which are stocked from Federal fish hatcheries at Garrison, Gavins Point, and Spearfish. In 1964, these hatcheries released almost 5 million rainbow trout fingerlings into Lake Sharpe. During the winter, icefishing shacks known as Missouri River Hiltons are towed onto the ice. Many have gas heaters, stoves, and other comforts.

At Gavins Point, the District helped popularize fishing. To keep the reservoir area clean, the District erected a building in which anglers could clean their catch. Previously, many had left the heads and entrails to decay on the shore. The new shelter, with electric lights, countertops, water, sewage disposal, and garbage cans, helps preserve the recreation complex for all.

In many ways, the laws, expenditures, and engineering efforts that transformed the shores of the Missouri and its tributaries also changed the lives of the people of the basin. These efforts created opportunities for the enjoyment of a wide variety of outdoor sports - from boating and camping to hunting and fishing.