The Rapid City Flood, June 1972

|

|

Courtesy Lincoln-Mercury, Inc., Rapid City. Graphic Restoration by Al Barrus

|

The citizens of Rapid City, South Dakota, thought of their visitors and themselves when they won Works Progress Administration funding in the 1930's to build Canyon Lake Dam on Rapid Creek. The 1,000-foot-long dam was built on the edge of the city. With a 70-foot base and 30-foot crown, the 20-foot-high dam backed up a 40-acre lake for recreation. The lake was great for fishing and boating, but the dam's 3.5-foot free-board was inadequate for containment of any substantial flood.

As Rapid City grew, so did the need for drinking water. Deerfield Dam on Castle Creek, built during the 1940's, supplied that need but still did not give complete flood protection. When nearby Ellsworth Air Force Base became a Strategic Air Command facility, the larger Pactola Dam was built. Authorized under the Pick-Sloan plan, Pactola was just a few miles above the city on Rapid Creek. This large earth-fill dam stored water for drinking, irrigation, and recreation and had a free-board to contain floodwater.

The Cheyenne River, which receives the waters of Rapid Creek, has flooded 33 times since 1878. Snow melt contributes to the flooding of the river, but intense thunderstorms are more likely to cause high water. The most damaging of the Cheyenne's floods rose on Rapid Creek during 12 and 13 June 1907. The storm centered on Fort Meade, north of Rapid City and close to Sturgis. It dumped over seven inches of rain on the area.

|

| Pumping at pool behind Ft. Meade Dam |

Such storms are dangerous. In 1957, the Corps of Engineers proposed flood control projects at Belle Fourche, Spearfish, New Underwood, Sturgis, and Rapid City. The Corps wanted to channelize Rapid Creek at Rapid City to carry 6,000 c.f.s., only half of what the 1907 flood dumped into the stream. To get the project, the citizens of Rapid City had to buy rights-of-way and lengthen nine highway bridges. They blanched at the $2.7 million price tag and, like their fellow citizens everywhere in the Black Hills except Belle Fourche, decided not to help build the project. As a result, none of the projects were built before 1972.

Working under the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968, the Soil Conservation Service delineated Rapid Creek's flood plain. With proper legislation and zoning laws, this designation helped make the area's inhabitants eligible for Federal flood insurance. The city quickly passed the laws and zoning regulations to qualify for the insurance; however, few residents bought the protection. By early 1972, the city took flood control measures, bought three blocks of land along Rapid Creek, and moved 22 families from them. The beginning of a "green-way," an urban flood way, was thus set afoot.

The occurrences of 9 and 10 June 1972 surprised and shocked Rapid City. A southeast breeze pushed the mass of moist air that hung over the high plains up against the Black Hills. Then it began to rain. The airport at Rapid City recorded 2.75 inches; a station to the south noted 3.5 inches. Pactola Dam got nearly six inches, and the little town of Nemo to the northwest gauged seven inches in six hours. Isobar maps of the storm showed that some of the areas in the vicinity received 14 inches. No one anticipated such a deluge.

|

| 5th Army opening road to stranded town |

By 7 p.m., flood waters rolled over the high ground north of Rapid City. Mayor Don Barnett began appealing to campers to seek safety. Inside the town itself, few people took seriously the warnings of impending danger. Before midnight, water poured into picturesque Canyon Lake. At the flood's peak,the narrow canyon carried 50,000 c.f.s., or roughly 1.5 times the normal volume of the Missouri at Omaha.

The runoff turned Rapid, Boxelder, and Boulder Creeks into raging rivers, and the old Fort Meade Dam at Sturgis nearly collapsed. The rain below Pactola Dam gathered in Dark Canyon. Rapid Creek ran through the canyon, flowed onto the plain, and normally followed a lazy curve. But on June 9, the roaring waters simply rushed straight ahead into the Swiss Chalet subdivision. Only three of the 42 homes in the development survived the flood. The bridge that carried Highway 40 over the creek was 18 feet above bed, but the wall of water that swamped it and tore it away was over 20 feet high.

|

| Nebraska National Guard, Omaha World Herald photo |

Mobile homes were torn away from their moorings, tossed about on the waters like matchboxes, and carried into Canyon Lake. Some smashed into the dam embankment, weakening it. At midnight, the battered structure was over-topped, the cascading water washed its earthen slope away, and a five-foot wall of water descended on the sleeping residents of the town. Slabs of concrete and pavement the size of house walls floated on the water. Rushing down the valley and through the plain, the torrent destroyed bridges, tore away telephone poles, broke gas mains, and cut the town in two.

Among those who lost their homes to the debris-choked waters was Mrs. Francis Case. She was the widow of the South Dakota Senator who had done so much through his office to mitigate the damages caused by floods. Case had seen that the Red Dale Gulch Dam outside Rapid City was built to protect others from floods. When his widow returned to her home, most of it was gone. Four of her neighbors' homes had also been swept away. "I don't think anyone would want to live out here again," she said dejectedly. "I guess I will just have to start over again."

|

| Food and supplies arrive for stranded families, World-Herald photo |

Dawn came over wet and leaden clouds to find an automobile perched crazily atop a huge sundial in Canyon Lake Park. The gray light shone on 1,800 tired and wet South Dakota National Guardsmen who had been frantically engaged in rescue work throughout the night. They had been undergoing their annual two-week training duty at Camp Rapid on the outskirts of the city. Airmen from nearby Ellsworth came in to assist, and troops were on their way from Fort Carson.

South Dakota's adjutant general, Major General Duane L. Corning, had difficulty moving his troops the very short distance into town. The bridges on Interstate 90 were out. Highway 40, which shared the flood plain with Rapid Creek, also lost its bridges. The Interstate 190 business loop was available, but large boulders blocked the streets while dangling bridges hampered the rescue effort. Five blocks of homes paralleling the creek were gone, and 80 blocks of pavement were torn Up.

The light of day' revealed the devastation. One-third of the city had been under from five to 10 feet of water. Wreckage was strewn everywhere. Some signs of panic and desperation were seen. Cases of looting were reported, and a group of bystanders was shot at from a passing car. Men and women in drenched civilian clothing directed traffic for the overburdened police force. Mayor Barnett imposed a 9 p.m. curfew, and Police Chief Ronald Messer called for 1,500 military policemen to maintain order.

|

| South Dakota National Guardsmen |

Initially, it was presumed that 155 people had drowned, but the final count was 244. Five hundred more were missing and 5,000 were homeless. Two National Guardsmen were among the missing, as were three firemen who vanished while fighting a house fire caused by leaking gas. Rushing water pushed the house off of its foundation, and the dwelling smashed into the firemen, shoving them into the rushing waters of Rapid Creek.

In Sturgis, flood-waters destroyed five homes, damaged 50, and pushed many mobile homes off of their foundations while filling them with mud. On Bear Butte Creek, a motel was extensively damaged, and park facilities were demolished. Bridge approaches and portions of Highway 14A between Deadwood and Boulder Canyon washed out. All of north Sturgis was covered with water while many streets were damaged, their surfaces broken and covered with debris. No lives were lost in Sturgis, but the Red Cross gave over 800 typhoid shots and patients, staff, and residents of the Sturgis Community Hospital and Community Nursing Home were moved to the Fort Meade Veterans Hospital and McKee Nursing Home. Some Sturgis residents went to Rapid City as volunteers because the damage there was greater than in their own town.

After receiving confirmation of the damages, President Richard M. Nixon declared the Black Hills and Rapid City as disaster areas. Immediately, Federal agencies focused their attention on the town. Director of the Office of Emergency Preparedness George Lincoln and Presidential adviser Robert Finch flew to Rapid City to assess the damage.

|

| South Dakota National Guardsmen |

|

| Four Presidents' Motel at Highway 16 at Keystone, South Dakota, had to be torn down. |

|

| Park facilities demolished |

Several Federal offices offered aid to the victims. Food stamps were quickly made available to the victims of the flood by the Department of Agriculture. The Department of Housing and Urban Development brought in mobile homes as temporary shelters. The Small Business Administration and Farmers Home Administration provided low-cost loans to those whose homes and businesses had been destroyed.

The Corps of Engineers already had personnel on the scene from its area office at Ellsworth Air Force Base. When the Omaha District Office received word of the disaster, a team quickly flew to the area. District staffers established their emergency headquarters at the South Dakota School of Mines. They quickly gathered evidence to establish the flood as a "class A" emergency, under which all of the Corps' skills could be brought to bear. Almost immediately, the Corps team contacted the Associated General Contractors of South Dakota to determine the availability of crews and construction equipment. The team, led by the District Engineer, Colonel Billy P. Pendergrass, directed the builders in the dirty business of removing debris and cleaning up the city.

After the Corps' damage assessment teams surveyed the area, Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth B. Austin, the Deputy District Engineer, awarded 11 contracts for debris removal. Ten covered Rapid City and the 11th Fort Meade. The cleanup was the first step toward putting the city back on its feet.

In addition to the 2,500 guardsmen who worked 12-hour shifts on the cleanup, volunteers, organized in platoons of 20, participated in the effort. Each platoon was assigned to one of 58 devastated blocks along a one-mile stretch of the creek. The municipal auditorium and Central High School auditorium were filled with tables stacked with necessities to help the victims. Hot dishes, sandwiches, and salads were set out on the auditorium tables to feed the volunteers and the homeless.

|

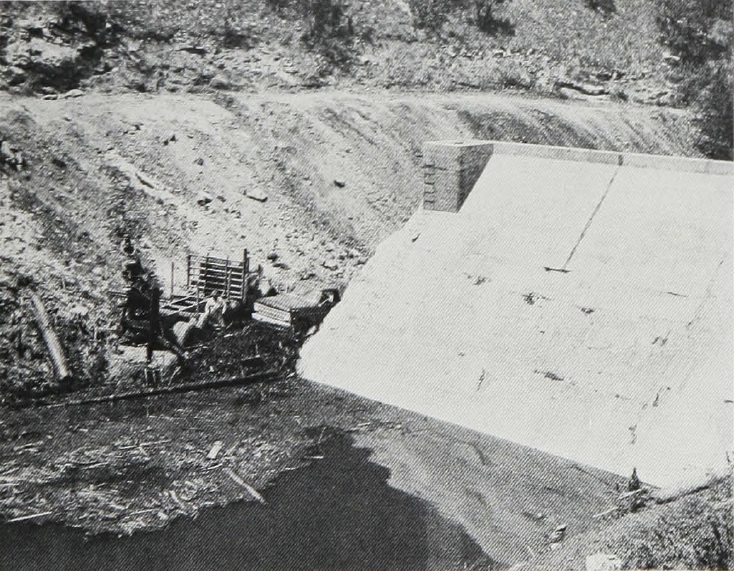

| Explosives in place on right abutment of Fort Meade Dam |

As the Army's civil works agent, the Omaha District had responsibility for the Fort Meade Dam. The 69-year-old structure near Sturgis straddled Deadman Gulch and Deadman Creek. At one time, the lake behind the dam had supplied the local Veterans' Administration hospital with water. In June 1972, the dam, which was 215 feet wide and 56 feet high and stored 21 million gallons of water, had a different purpose; it supplied a modicum of protection against floods. The torrential Friday rains over-topped the dam, washed away much of its face, and tore away a section of the crest. The District quickly went to work to restore Fort Meade. The spillway was widened, while pumps flown in from Kansas City drew the reservoir down to 10 feet. The pumping was painfully slow, but the removal of water from the lake significantly diminished the pressure on the dam's base. The situation there still remained critical. As one engineer said, "If it does not rain by Friday, odds are very good the dam will hold. If it rains, we do not have much odds."

Despite these efforts, too much water remained behind the dam. If it burst, a wall of water would inundate the lower end of Sturgis. Families were evacuated from the threatened area. The town's fire siren was manned at all times to give a 12-minute warning if the rains came and the dam broke.

Deputy District Engineer Austin came to Sturgis with Walter Linder and J.F. Kelley and examined the data. They met with the townspeople concerning the structure's fate. The three wanted to breach the dam, which they considered a menace. Acutely aware of what had happened at Rapid City, the residents wanted to keep it to hold back the water.

As the draw-down continued, Austin and the engineers went against the wishes of the townspeople. They had a special team flown in from the Corps' Explosive Excavation Research Laboratory in Livermore, California. Under darkening skies, the decision was made to destroy the dam rather than risk the break that could cause a 10-foot wall of water to roar through Sturgis. The experts placed 3,000 pounds of explosives at selected spots on the structure. The blast, accompanied by a 200-foot fireball, blew a wedge 20 feet wide at the dam's base and 80 feet wide at the crest. The rubble was cleared and one threat was eliminated.

Eight days after the downpours that brought the flood-waters, there was again high water. In the early evening the rains came, and Rapid Creek went slowly out of its banks. Again, Mayor Barnett declared martial law, and low-lying areas were evacuated. While many people moved to higher ground, others sought the dangerous refuge of their roofs. Many of their belongings, which had been spread on lawns to dry, were again covered with silt. A panel truck carrying six people plunged into a ditch, and two of the occupants drowned. The struggle to bring the town back to a semblance of normality was underway. Civil defense emergency headquarters in the Pennington County Courthouse helped in the effort to obtain stability. Local law enforcement agencies replaced the military in authority and the job of damage assessment continued.

The local chapters of the National Association of Professional Engineers and the American Institute of Architects assisted in the evaluation. The assessors used aerial photographs and classified public and private property losses. Public losses consisted of city and county property, such as emergency health facilities, streets and bridges, public buildings, utilities, and schools. The estimated value was $38 million. Private individuals lost residential and business buildings, mobile homes, vehicles, roads, sidewalks, and sewers. The cost of cleaning up the mess amounted to $35 million.

|

| After explosion showing structure gap |

|

| Cleanup after blast-cutting |

The total loss figure did not include other costs. The Department of Housing and Urban Development supplied $8 million in temporary housing. The State of South Dakota and the U.S. Department of Labor paid over $250,000 in unemployment benefits. The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare - now the Department of Health and Human Services - spent another $100,000 to repair schools, while the Department of Transportation and the Forest Service paid a total of about $20 million for road repair. Total Federal expenditures were nearly $165 million.

Corps of Engineers cleanup operations continued after the waters subsided. The Corps awarded and supervised 44 contracts for the removal of over 1.2 million cubic yards of silt and debris at a cost of almost $2 million. Local governments spent an additional $1.5 million on debris removal. For this they were reimbursed by the Office of Emergency Preparedness.

The disaster at Rapid City influenced enactment of a national dam safety program. Public Law 92-367, passed in August 1972, required the Corps of Engineers to inspect every dam in the country which threatened life or property and also to inspect dams with high downstream hazard potential. Whenever hazardous conditions are found within a dam, the Corps is required to report them to the Governor of the state in which the dam is located.

|

| Removal of debris |

After the flood, the breached Canyon Lake structure remained unaltered for about two years while the recovery effort focused on getting the urban renewal plan and its green-way started. However, rebuilding the dam was always part of the city's plan. The city initially planned to rebuild the dam the way it was before the flood. The Corps convinced the Mountain Plains Federal Regional Council (FRG) that the dam had to be reconstructed according to hydraulic and hydro-logic criteria acceptable to the Corps. Because the recovery plans relied mostly on Federal funds, the city complied. The dam was redesigned by the city and reconstructed to allow passage of a flood larger than that of 1972.

Flood control and other water resources problems in the Cheyenne River basin had been previously evaluated. In 1971, a Corps review concluded that no structural measures could be economically justified in the basin. That report was under review by the Missouri River Division when the June 1972 flood occurred. The Division Engineer returned the report and asked that the Omaha District reevaluate the findings considering the effects of the June 1972 flood.

The devastation made painfully clear the need for positive action by all levels of government. The Mountain Plains FRC quickly moved into action as the coordinating body for the Federal agencies. With the Governor of South Dakota, it quickly established that the strategy for redevelopment would be fashioned by local officials and that Federal and State programs would be tailored as a response to local priorities. The Corps was invited to join the FRC. An assessment of needs was developed by local, regional, and State planning officials. From this listing of priorities, a Federal disaster response plan ultimately developed.

The Corps played a very critical role in determining the direction of major redevelopment plans. The Corps was given 60 days to totally reevaluate the findings of the 1971 study and to specifically determine if structural measures could be justified. Other Federal agencies agreed to make no major moves on redevelopment programs before the Corps' decision. On August 2 and 3, the District held public meetings in Rapid City and presented its findings.

|

| Note cars in Canyon Lake bed, 16 June 1972 |

The Corps concluded that a flood-way with some minor structural improvements was the most viable course of action for the city. Furthermore, a channel improvement project on Deadman Gulch at

Sturgis would be feasible, and flood proofing or flood insurance appeared to be the best solutions at Keystone and Box Elder, South Dakota. While the Corps evaluation was underway, the Department of Housing and Urban Development prepared preliminary urban renewal plans for Rapid City and Sturgis. Immediately after the Corps' public meetings in August 1972, both cities applied for urban renewal funds for greenbelts that would serve as floodways for the 100-year flood areas.

|

| Flood damages from Deadman Gulch at Sturgis, South Dakota, in 1976 |

|

In Rapid City, the urban renewal plan called for the Corps to construct levees and channel improvements for the Baken Park Shopping Center, Clarkson Mountain View Guest Home, Bennett-Clarkson Hospital, and the municipal water treatment plant as integral parts of the plan. These facilities were considered too costly to relocate from the floodway.

The land for Rapid City's six-mile floodway was acquired through the purchase of 1,100 parcels of land containing 3,100 acres and costing $48 million. The city, with the help of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, purchased the floodway to establish nature areas and trails, layout a golf course, grade ballfields, and create a memorial path. The Levee Design Section of the District's Engineering Division designed and built a 4,000-foot levee to protect the west-end shopping area. Any future flood will sweep over only grass and recreational equipment. The contoured levees and channel improvements on Rapid Creek were completed in 1979 for $1.35 million.

Immediately after the Rapid City flood, the citizens of Sturgis contacted the Omaha District to ascertain what could be done to protect their town from a similar occurrence. The South Dakotans had seen the dam at Fort Meade threaten them and had sustained almost $3 million in damages during the 1972 flood. Another flood struck Sturgis in 1976 and caused $2 million in damages. There was no question then that the town needed flood protection on Deadman Gulch, that economically feasible protection could be provided, or that the town wanted such protection.

The District prepared a flood protection project plan that became an integral part of Sturgis' urban renewal plan. On 1 June 1976, the Chief of Engineers allotted $3 million to the $4.1 million project which included training levees above the town, channelization of the stream through a concrete canal, and construction of a debris basin upstream and a stilling basin where Deadman Gulch empties into Bear Butte Creek.

The Sturgis project was dedicated in September 1979. In November 1979, District Engineer Colonel Vito D. Stipo and his deputy, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas R. Hicklin, inspected the project. They found that close cooperation between the District's project engineer, B.J. Burt; the town of Sturgis; and the COP Construction Company had been responsible for the virtual completion of the project a year ahead of schedule. Both Stipo and Hicklin were pleased with the contractor's performance and with the results.

The newly created channel follows the local topography and drops 190 feet in elevation along its 6,600-foot course. Without training works, such a steep slope would allow destructively rapid runoff. After the planting of grass seed along the channel, the project was formally turned over to Sturgis on 26 June 1980.